When we first met, I was a child, and she had been dead for centuries.

Look: I am eleven, a girl who is terrible at sums and at sports, a girl given to staring out windows, a girl whose only real gift lies in daydreaming. The teacher snaps my name, startling me back to the flimsy prefab. Her voice makes it a fine day in 1773, and sets English soldiers crouching in ambush. I add ditchwater to drench their knees. Their muskets point toward a young man who is tumbling from his saddle now, in slow, slow motion. A woman rides in to kneel over him, her voice rising in an antique formula of breath and syllable the teacher calls a “caoineadh,” a keen to lament the dead. Her voice generates an echo strong enough to reach a girl in the distance with dark hair and bitten nails. Me.

In the classroom, we are presented with an image of this woman standing alone, a convenient breeze setting her as a windswept, rosy-cheeked colleen. This, we are told, is Eibhlín Dubh Ní Chonaill, among the last noblewomen of the old Irish order. Her story seems sad, yes, but also a little dull. Schoolwork. Boring. My gaze has already soared away with the crows, while my mind loops back to my most-hated pop song, “and you give yourself away … ” No matter how I try to oust them, those lyrics won’t let me be.

*

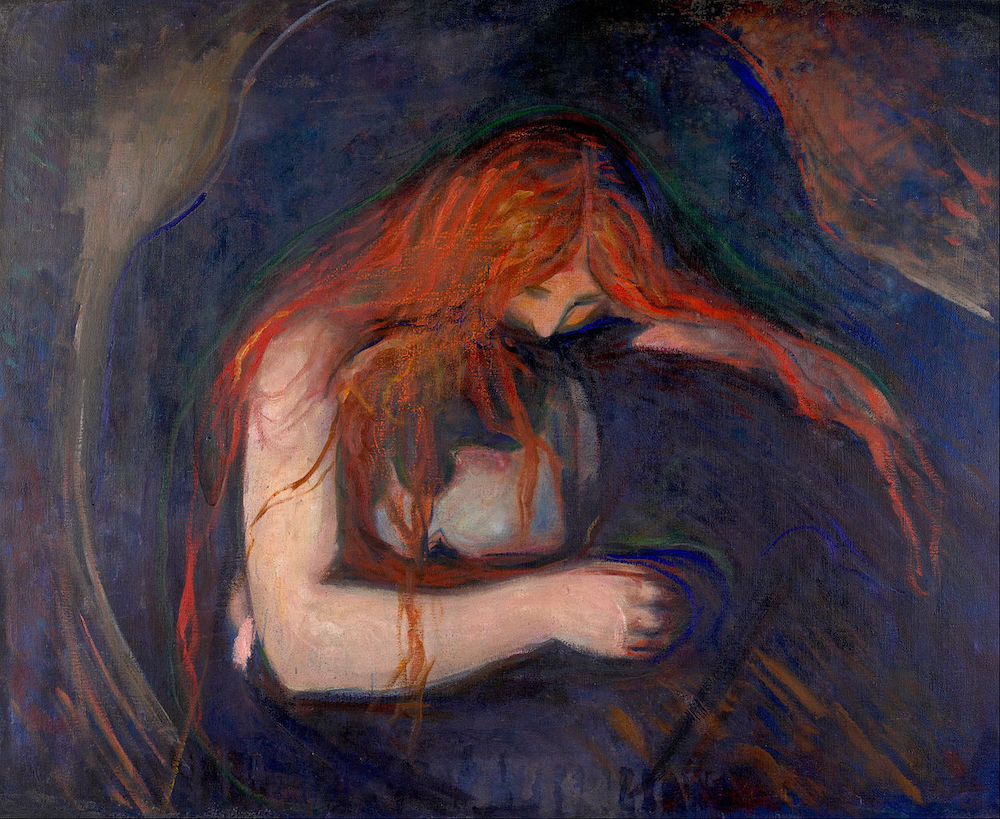

By the time I find her again, I only half-remember our first meeting. As a teenager I develop a schoolgirl crush on this caoineadh, swooning over the tragic romance embedded in its lines. When Eibhlín Dubh describes falling in love at first sight and abandoning her family to marry a stranger, I love her for it, just as every teenage girl loves the story of running away forever. When she finds her murdered lover and drinks handfuls of his blood, I scribble pierced hearts in the margin. Although I don’t understand it yet, something ricochets in me whenever I return to this image of a woman kneeling to drink from the body of a lover, something that reminds me of the inner glint I feel whenever a boyfriend presses his teenage hips to mine and his lips to my throat.

My homework is returned to me with a large red X, and worse, the teacher’s scrawl cautions: “Don’t let your imagination run away with you!” I have felt these verses so deeply that I know my answer must be correct, and so, in righteous exasperation, I thump page after page down hard as I make my way back to the poem, scowling. In response to the request “Describe the poet’s first encounter with Art Ó Laoghaire,” I had written: “She jumps on his horse and rides away with him forever.” But on returning, I am baffled to find that the teacher is correct: this image does not exist in the text. If not from the poem, then where did it come from? I can visualize it so clearly: Eibhlín Dubh’s arms circling her lover’s waist, her fingers woven over his warm belly, the drumming of hooves, and the long ribbon of hair streaming behind her. It may not be real to my teacher, but it is to me.

*

If my childhood understanding of this poem was, well, childish, and my teenage interpretation little more than a swoon, my readings swerved again in adulthood. I had no classes to attend anymore, no textbooks or poems to study, but I had set myself a new curriculum to master. In attempting to raise our family on a single income, I was teaching myself to live by the rigors of frugality. I examined classified ads and supermarket deals with care. I met internet strangers and handed them coins in exchange for bundles of their babies’ clothes. I sold bundles of our own. I roamed car boot sales, haggling over toddler toys and stair gates. I only bought car seats on sale. There was a doggedness to be learned from such thrift, and I soon took to it.

My earliest years of motherhood, in all their fatigue and awe and fretfulness, took place in various rented rooms of the inner city. Although I had been raised in the countryside, I found that I adored it there: the terraces of smiling neighbors with all their tabbies and terriers, all our bins lined up side by side, the overheard cries of rage or lust in the dark, and the weekend parties with their happy, drunken choruses. Our taps always dripped, there were rats in the tiny yard, and the night city’s glimmering made stars invisible, but when I woke to feed my first son, and then my second, I could split the curtains and see the moon between the spires. In those city rooms, I wrote a poem. I wrote another. I wrote a book. If the poems that came to me on those nights might be considered love poems, then they were in love with rain and alpine flowers, with the strange vocabularies of a pregnant body, with clouds and with grandmothers. No poem arrived in praise of the man who slept next to me as I wrote, the man whose moonlit skin always drew my lips toward him. The love I held for him felt too vast to pour into the neat vessel of a poem. I couldn’t put it into words. I still can’t. As he dreamed, I watched poems hurrying toward me through the dark. The city had lit something in me, something that pulsed, vulnerable as a fontanelle, something that trembled, as I did, between bliss and exhaustion.

We had already moved twice in three years, and still the headlines reported that rents were increasing. Our landlords always saw opportunity in such bulletins, and who could blame them? Me. I blamed them every time we were evicted with a shrug. No matter how glowing their letters of reference, I always resented being forced to leave another home. Now we were on the cusp of moving again. I’d searched for weeks, until eventually I found a nearby town with lower rents. We signed another lease, packed our car, and left the city. I didn’t want to go. I drove slow, my elbow straining to change gear, wedged between our old TV and a bin-bag of teddies, my voice leading a chorus through “five little ducks went swimming one day.” I found my way along unfamiliar roads, “over the hills and far away,” scanning signs for Bishopstown and Bandon, for Macroom and Blarney, while singing “Mammy Duck said Quack, Quack, Quack … ” until my eye tripped over a sign for Kilcrea.

Kilcrea—Kilcrea—the word repeated in my mind as I unlocked a new door, it repeated and repeated as I scoured dirt from the tiles, and grimaced at the biography of old blood and semen stains on the mattresses. Kilcrea, Kilcrea, the word vexed me for days, as I unpacked books and coats and baby monitors, spoons and towels and tangled phone chargers, until finally, I remembered—Yes!—in that old poem from school, wasn’t Kilcrea the name of the graveyard where the poet buried her lover? I cringed, remembering my crush on that poem, as I cringed when I recalled all the skinny rockstars torn and tacked onto my teenage walls, the vocabulary they allowed me to express the beginnings of desire. I flinched, in general, at my teenage self. She made me uncomfortable, that girl, how she displayed her wants so brashly, that girl who flaunted a schoolbag Tipp-Exed with longing, who scribbled her own marker over layers of laneway graffiti, who stared obscenely at strangers from bus windows, who met their eyes and held them until she saw her own lust stir there. The girl caught in forbidden behaviors behind the school and threatened with expulsion. The girl called a slut and a whore and a frigid bitch. The girl condemned to “silent treatment.” The girl punished and punished and punished again. The girl who didn’t care. I was here, singing to a child while scrubbing old shit from a stranger’s toilet. Where was she?

*

In the school car park, I found myself a little early to pick up my eldest and sought shelter from the rain under a tree. My son was still dreaming under his plastic buggy cover, and I couldn’t help but admire his ruby cheeks and the plump, dimpled arms I tucked back under his blanket. There. In the scrubby grass that bordered the concrete, bumblebees were browsing—if I had a garden of my own, I thought, I’d fill it with low forests of clover and all the ugly weeds they adore, I’d throw myself to my knees in service to bees. I looked past them toward the hills in the distance, and, thinking of that road sign again, I rummaged for my phone. There were many more verses to the caoineadh than I recalled, thirty, or more. The poem’s landscape came to life as I read, it was alive all around me, alive and fizzing with rain, and I felt myself alive in it. Under that drenched tree, I found her sons, “Conchubhar beag an cheana is Fear Ó Laoghaire, an leanbh”—which I translated to myself as “our dotey little Conchubhar / and Fear Ó Laoghaire, the babba.” I was startled to find Eibhlín Dubh pregnant again with her third child, just as I was. I had never imagined her as a mother in any of my previous readings, or perhaps I had simply ignored that part of her identity, since the collision of mother and desire wouldn’t have fitted with how my teenage self wanted to see her. As my fingertip scar navigated the text now, however, I could almost imagine her lullaby hum in the dark. I scrolled the text from beginning to end, then swiped back to read it all again. Slower, this time.

The poem began within Eibhlín Dubh’s gaze as she watched a man stroll across a market. His name was Art and, as he walked, she wanted him. Once they eloped, they led a life that could only be described as opulent: oh, the lavish bedchambers, oh, the delectable meals, oh, the couture, oh, the long, long mornings of sleep in sumptuous duck-down. As Art’s wife, she wanted for nothing. I envied her her home and wondered how many servants it took to keep it all going, how many shadow women doing their shadow work, the kind of shadow women I come from. Eibhlín dedicates entire verses to her lover in descriptions so vivid that they shudder with a deep love and a desire that still feels electric, but the fact that this poem was composed after his murder means that grief casts its murk-shadow over every line of praise. How powerful such a cataloging must have felt in the aftermath of his murder, when each spoken detail conjured him back again, alive and impeccably dressed, with a shining pin glistening in his hat, and “the suit of fine couture / stitched and spun abroad for you.” She shows us Art as desired, not only by herself, but by others, too, by posh city women who

always

stooped their curtsies low for you. How well, they could see

what a hearty bed-mate you’d be,

what a man to share a saddle with,

what a man to spark a child with.

Although the couple were living through the regime of fear and cruelty inflicted by the Penal Laws, her husband was defiant. Despite his many enemies, Art seemed somehow unassailable to Eibhlín, until the day that “she came to me, your steed, / with her reins trailing the cobbles, / and your heart’s blood smeared from cheek to saddle.” In this terrifying moment, Eibhlín neither hesitated nor sought help. Instead, she leaped into that drenched saddle and let her husband’s horse carry her to his body. In anguish and in grief, then, she fell upon him, keening and drinking mouthfuls of his blood. Even in such a moment of raw horror, desire remained—she roared over his corpse, ordering him to rise from the dead so she might “have a bed dressed / in bright blankets / and embellished quilts / to spark your sweat and set it spilling.” But Art was dead, and the text she composed became an evolving record of praise, sorrow, lust, and reminiscence.

Through the darkness of grief, this rage is a lucifer match, struck and sparking. She curses the man who ordered Art’s murder: “Morris, you runt; on you, I wish anguish!— / May bad blood spurt from your heart and your liver! / Your eyes grow glaucoma! / Your knee-bones both shatter!” Such furies burn and dissipate and burn again, for this is a poem fueled by the twin fires of anger and desire. Eibhlín rails against all involved in Art’s betrayal, including her own brother-in-law, “that shit-talking clown.” Rage. Rage and anguish. Rage and anguish and love. She despairs for her two young sons, “and the third, still within me, / I fear will never breathe.” What losses this woman has suffered. What losses are yet to come. She is in pain, as is the poem itself; this text is a text in pain. It aches. When the school bell rang, my son found me in the rain, my face turned toward the hills where Eibhlín Dubh once lived.

That night, the baby squirmed inside me until I abandoned sleep, scrambling for my phone instead. My husband instinctively curled his sleeping body into mine; despite his snores, I felt him grow hard against the dip of my back. I frowned, holding very still until I was sure he was asleep, then inching away to whisper the poem to myself, conjuring a voice through hundreds of years, from her pregnant body to mine. As everyone else dreamed, my eyes were open in the dark.

Doireann Ní Ghríofa is a poet and essayist. In addition to A Ghost in the Throat, she is the author of six critically acclaimed books of poetry, each a deepening exploration of birth, death, desire, and domesticity. Awards for her writing include a Lannan Literary Fellowship, the Ostana Prize, a Seamus Heaney Fellowship, and the Rooney Prize for Irish Literature.

From A Ghost in the Throat, by Doireann Ní Ghríofa. Copyright © Doireann Ní Ghríofa, 2020. Reprinted by permission of Biblioasis.